The Food and Drug Administration on Tuesday proposed requiring new nutrition labels on the front of food and beverage products, a long-awaited move aimed at changing eating habits associated with soaring rates of obesity and diet-related illness that are responsible for a million deaths each year.

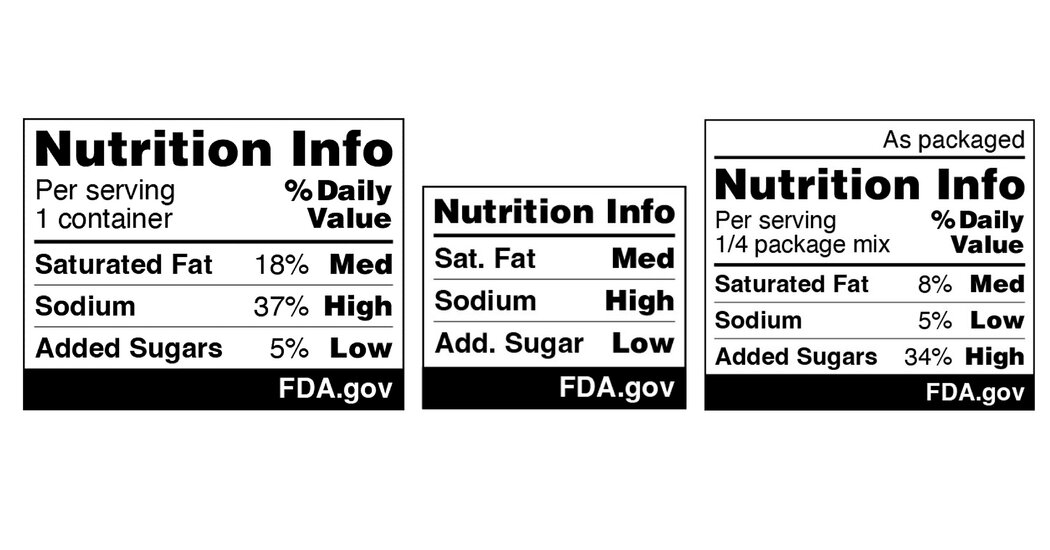

The new label, a small black-and-white box similar to the Nutrition Facts box on the back of packaged goods, is designed to help consumers quickly understand which products contain excessive amounts of sugar, salt and saturated fat. Those three nutrients are implicated in the nation’s skyrocketing rates of Type 2 diabetes, heart disease and high blood pressure.

More than 60 percent of American adults suffer from those three chronic illnesses, which are estimated to account for $4.5 trillion in annual health care costs, according to the F.D.A.

In contrast to the mandatory back-of-package Nutrition Facts panels, which list a product’s ingredients, calorie count and serving size, the front-of-package labels would rank the contents of sugar, fat and salt as high, medium or low to indicate whether the amounts exceed or fall short of the recommended daily values set by the F.D.A.

“Nearly everyone knows or cares for someone with a chronic disease that is due, in part, to the food we eat,” Dr. Robert Califf, the commissioner of the F.D.A., said in a statement. “It is time we make it easier for consumers to glance, grab and go.”

The proposal follows three years of research by agency scientists, who considered the front-of-package labels used by other countries. After reviewing studies on the effectiveness of those labels, the F.D.A. tested prospective designs with focus groups to determine whether the information they conveyed was easy to comprehend.

The proposed new labels scored highest among the 10,000 people who participated in the focus groups, the agency said.

Food companies would have up to four years to comply with the rules, if they were finalized. It is unclear whether they would continue under the incoming Trump administration.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Mr. Trump’s pick to lead the Department of Health and Human Services, has been vocal about the nation’s increasing reliance on ultra-processed foods and has pledged to transform American eating habits.

Nutrition experts said they were generally pleased by the look and the content of the new labels, but some expressed disappointment that they did not convey more forceful warnings when a product had unhealthy levels of salt, sugar and saturated fat. Some had also pressed the F.D.A. to include information about calories.

“This proposal is a real step forward in our efforts to better inform consumers, although we wish the administration had selected a nutrition warning format which is more likely to favorably affect purchasing decisions,” said Peter Lurie, the executive director of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, an advocacy group that first petitioned the F.D.A. to adopt front-of-package labels in 2006.

Food and beverage companies criticized the new rule, saying they would have preferred an industry-crafted version called Facts up Front, a voluntary labeling scheme introduced in 2011.

In a statement, Sarah Gallo, the senior vice president for product policy at the Consumer Brands Association, which represents many companies, said the proposed labels lacked important information like calorie count and whether a product contained high levels of nutrients key to a healthy diet.

“The F.D.A.’s proposed rule for front-of-package nutrition labeling appears to be based upon opaque methodology and disregard of industry input and collaboration,” Ms. Gallo said.

The announcement, issued in the final days of the Biden Administration, follows two decades of pressure from nutritionists, doctors and public health advocates, who had long urged the federal government to take a more assertive role in helping consumers make healthier choices as they dashed through supermarket aisles.

The new front-of-package rules complement other recent efforts by the F.D.A. to improve the nation’s eating habits. Last month, the agency updated the definitions of the term “healthy” for labeling on foods, which tightened limits on saturated fat, sugar and salt in food. In August, the F.D.A. issued voluntary guidelines aimed at pressing food manufacturers to lower the amount of sodium in processed and packaged goods.

Some said the proposed labels were too timid.

Senator Bernie Sanders, an independent of Vermont, called them “pathetically weak” because they did not clearly convey the health risks of ultra-processed foods, which by some estimates make up nearly 70 percent of the calories consumed by children and teens and 60 percent of those by adults.

“The proposed F.D.A. rule fails to adequately warn the American people of the dangers of consuming these unhealthy products,” he said in a statement.

But some experts say mandatory front-of-package labels may also encourage food manufacturers to reformulate products with high levels of unhealthy nutrients.

“If you’re a retailer selling something that’s just above the threshold, you have a lot of incentive to take a little bit of sugar out of your breakfast cereal so it doesn’t bear the high label,” said Anna Grummon, the director of the Stanford Food Policy Lab. “That’s a win for consumers.”

A number of studies have highlighted the limitations of the Nutrition Facts panel, which was introduced in the mid-1990s. Lauren Fiechtner, the director of nutrition at MassGeneral Hospital for Children, said many Americans, especially those with lower levels of education, found it hard to understand the existing labels. Most confounding, studies have found, are the label’s references to an ingredient’s percentage of recommended daily value.

“When I’m rushing down the grocery store aisle with my two young children, it’s challenging to turn over every package and understand the labels, and this is my job,” Dr. Fiechtner said. “Consumers want to be informed, but you have to keep it simple.”

Since 2016, when Chile became the first country to require packaged food companies to prominently display black warning logos on the front of packages, more than a dozen countries have adopted similar labels. They include Canada, Australia, Ecuador and the United Kingdom, according to the Global Food Research Program at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Nancy Glick, the director of food and nutrition policy at the National Consumers League, said studies showed that so-called interpretive labels influence consumer behavior. “These labels work, and what we’ve found is that people really want them,” she said.

Xaq Frohlich, a history professor at Auburn University and the author of the book “From Label to Table: Regulating Food in America in the Information Age,” had a somewhat cynical take on the new labels. He noted that the food industry had in the past found ways to adapt to labeling requirements by reformulating products in ways that were not necessarily healthier for consumers.

As an example, he said manufacturers of ultra-processed foods might replace added sugar with an artificial sweetener, allowing them to avoid the “high” label. But the reformulation, he said, would not make the product much healthier.

“It’s really hard to create the perfect label system that doesn’t create problems and unintended consequences,” he said. “There are good faith actors in the food industry who really use these labels to make their products healthier, but there are also a lot of bad faith actors who will tweak their processed food to look good on the label, but in fact, it won’t meet the spirit of what the F.D.A. and public health experts are seeking.”